A search for axions at the Large Hadron Collider

Harry Anthony, Anni Kauniskangas & Michael McCann

Beyond the Standard Model

A huge ambition for particle physicists is to create a mathematical framework that can describe all the basic constituents of matter and the forces that act between them. Our modern understanding of particle physics is currently best described by the Standard Model. The Standard Model has proven to be remarkably accurate, matching almost all experimental measurements to a very high accuracy for over 50 years.

Despite its many successes, physicists have observed several phenomena which the Standard Model cannot describe. For example, the Standard Model does not have a candidate for dark matter or dark energy - which combined make up approximately 95% of the Universe. Therefore, physicists have been trying to create extensions to the Standard Model which can explain these phenomena.

One particle, which is not in the Standard Model, that has been predicted is the Axion-Like Particle (ALP). ALPs are neutral massive particles, which were hypothesised to solve problems in theoretical physics. Moreover, light ALPs are potential dark matter candidates. Their discovery would be the first ever particle outside the Standard Model to be detected.

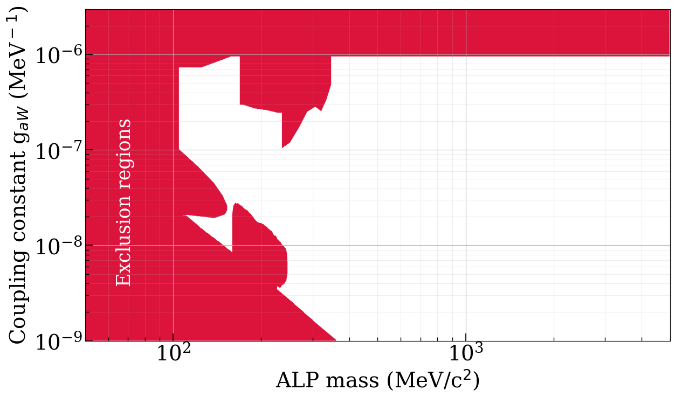

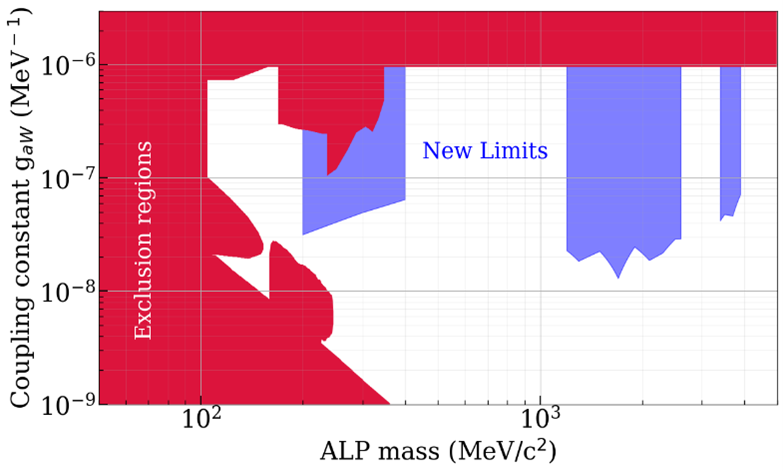

In theoretical models, ALPs can interact with another particle, the W± boson, which is in the Standard Model. The strength of the interaction between these two particles is measured by a coupling constant gaW. The coupling constant gaW can be used with the mass of an ALP to draw out a 2D map called parameter space (figure below). If our understanding of ALPs is correct, then ALPs should occupy an area of this map.

Experimental results allow us to block out areas of this map, known as exclusion regions, where an ALP could not be. However, there are still large areas of the parameter space which have not been explored yet, in particular the area of heavy ALPs.

How would we explore this region? Physicists believe we could find an ALP by studying rare decays of B mesons (mesons containing a beauty quark). One particular B meson decay shows promise for finding ALPs. During this decay, a W± boson is produced, which quickly decays into an ALP. These ALPs then decay into two photons, which can be detected. This decay allows us to study heavy ALPs, enabling us to study the unexplored parameter space.

Finding a needle in a haystack

The results were produced using data from the LHCb experiment, one of the four major particle detectors at the Large Hadron Collider, which is specifically designed to study B meson decays. CERN’s Large Hadron Collider is the most energetic particle accelerator in the World, which creates particles by smashing protons together at speeds very close to the speed of light. This produces billions of particles at the detector, which makes finding a particular decay in a sea of other particles like finding a needle in a haystack.

To search for the decay, scientists create simulations to mimic what a signal from the decay would look like. These simulations are then compared to data measured by the detector to remove any data that does not look like it came from the decay. To improve their search, scientists use machine learning algorithms. These algorithms can find patterns in the data (too complex for humans to find) which can be used to discriminate between data originating from the decay and data which did not.

This analysis did not find an ALP, however it found new exclusion region limits in the parameter space (blue areas in figure below), reducing the existing limits by over an order of magnitude. This result reduces the area of parameter space to look through for future ALP searches, taking us a step closer to finding or disproving ALPs.

Dive into our research!

| 📊 Poster |